Between the Best and the Worst: Some Thoughts on Not Surrendering

Dear readers,

I'm setting off in a couple of hours on an overnight trip with a friend to go visit our mutual friend, Jarvis Masters, who's one of the many prisoners moved off Death Row but not actually relieved of that murderous sentence. He's innocent of the crime for which he was sentenced forty years ago, a careful review of the evidence has convinced me and some very good lawyers, and he's a remarkable human being who's become a Buddhist practitioner (Pema Chodren loves him and visits), a beautiful writer (his powerful memoir That Bird Has My Wings was an Oprah Book Club selection a couple of years ago), and a remarkable person I'm lucky to know (there is nothing more mortifying than reciting your own tribulations to someone in his situation, so context is one of the things he gives me; fortunately he has a sense of humor too).

When Governor Newsom disbanded San Quentin's Death Row, he got moved to another prison and then to the present one where he has more freedom and more contact with the natural world, something he greatly missed all those years when his only outdoor time was in a walled yard in the middle of the day. He deserves far more, but I'm glad he got a little more, and hope to tell you more about what him after the visit (we'll drive down to San Luis Obispo today, visit and come home tomorrow).

But what I wanted to write about today is how we tell our stories and the world's stories. I wrote a piece for the Guardian for the tenth anniversary of the Paris climate treaty which was yesterday. It began:

Today marks the 10th anniversary of the Paris climate treaty, one of the landmark days in climate-action history. Attending the conference as a journalist, I watched and listened and wondered whether 194 countries could ever agree on anything at all, and the night before they did, people who I thought were more sophisticated than me assured me they couldn’t. Then they did. There are a lot of ways to tell the story of what it means and where we are now, but any version of it needs respect for the complexities, because there are a lot of latitudes between the poles of total victory and total defeat.

Nevertheless a number of people snarked away at me on the basis that if I didn't say we lost, I'd said we won. Of course the truth and the reality are often somewhere in the vast spaces inbetween.

The piece ended: Is this good enough? Far from it, but we are, as they say, “bending the curve”: before Paris the world was headed for 4 degrees of warming; it’s now headed for 2.5 degrees, which should only be acceptable as a sign that we have bent it and must bend more and faster. In the best-case scenario, the world’s leaders and powers would have taken the early warnings about climate change seriously and we’d be on the far side of a global energy transition, redesign of how we live, and protection of oceans, rainforests, and other crucial climate ecosystems. But thanks to valiant efforts by the climate movement and individual leaders and nations, we’re not in the worst-case scenario either. Landmarks like the Paris treaty and the Vanuatu victory matter, as do the energy milestones, and there’s plenty left to fight for. For decades and maybe centuries it has been too late to save everything, but it will never be too late to save anything.

A climate journalist I much admire came to my defense.

The grumpy old guy above was not alone. There was also Oliver, who jumped onboard Bill's grousing to say: "The only thing that has changed since the Paris Agreement Is that hundreds of fossil fuel lobbyists get an all-expenses paid holiday in a different COP country each year ensuring none of its recommendations are actually implemented." Which is wildly untrue about what the Paris agreement has achieved, and about what happens at the COPs (Conference of Parties annual climate meetings sponsored by the United Nations, at which representatives of nations, climate activists, and yes, those lobbyists all gather), and spectacularly untrue about all the other things that have changed since Paris, including countless pieces of legislation and the renewables revolution. It used to surprise me that what sounded like bitter cynicism was often naive at best about what had happened and what can happen.

Yet another extra-grumpy guy (they were all guys) insisted that my saying we were not in the worst-case scenario was callousness about those who've suffered and died because of climate change. I'm not sure he'd read the piece (often they haven't or they're just failing reading comprehension) because the piece celebrated most of all what people from the most impacted places – Vanuatu, the Philippines, the nations of the Climate Vulnerable Forum – have achieved. There's often a sense that defeatism, despair, general pessimism is a form of solidarity with the oppressed. I see that as the exact opposite of solidarity, because when we who are comparatively comfortable and safe give up, we give up on those who are most impacted. We decide there's nothing we can do about their suffering and oppression when there's lots we can do.

I wrote about that too, of course: "But you shouldn't mourn those who aren't dead. Doing so stuffs the living into coffins, at the very least in your imagination. Native North Americans, from the nineteenth century into the 1990s, were regularly told - through artworks and by bureaucrats and signage in museums and national parks and history books - that their cultural or literal demise was inevitable, that they were inevitably vanishing or already gone. Non-native people widely believed it. I have met Native people who were told to their face they and their culture were extinct. The people who said these things often saw themselves as sympathizing with those that they regard as history's victims, but told this story in ways that reinforced it."

Joshi made two really good points, one of which is that what I'm talking about is politics and the nature of power and change, which isn't necessarily something climate scientists have expertise in, and the other is that the activism I describe and encourage has made a difference. I am deeply committed, as everyone who knows me and my work knows, to encouragement, which a fellow writer once pointed out to me means to instill courage. I am trying as hard as I can to keep people from giving up. "Do not surrender in advance," said Timothy Snyder when Trump won the 2016 election (or at least the electoral college, while massively losing the popular vote). When it comes to the fossil fuel industry, doomers and defeatists serve them very well; they want us passive and uninvolved, out of their way.

The defeatists seem to think all encouragement is optimism or naivete or somehow illegitimate. One of the other guys who dumped on this piece on BlueSky decided that saying "In the best-case scenari,.. we’d be on the far side of a global energy transition, redesign of how we live, and protection of oceans, rainforests, and other crucial climate ecosystems. But thanks to valiant efforts by the climate movement and individual leaders and nations, we’re not in the worst-case scenario either" was morally wrong because climate change has caused so much death and suffering, but it's so often been those who are most impacted whose activism does the most. The piece leads off with the fantastic win in the International Court of Justice this July, led by Pacific Island nations severely threatened by sea-level rise and other climate impacts.

My Guardian piece actually unpacked how it all works: how the Climate Vulnerable Forum led what was supposed to be an unwindable fight to put 1.5 degrees in the treaty: It’s not widely known that most countries and negotiators went into the conference expecting to set a “reasonable” two-degree threshold global temperature rise we should not cross. As my friend Renato Redentor Constantino, a climate organizer in the Philippines, wrote:“The powerful exerted tremendous effort to keep a tiny number, 1.5, out of United Nations documents. 1.5 degrees centigrade represents what science advises as the maximum allowable rise in average global temperature relative to preindustrial temperature levels. It was the representatives of the mostly global-south nations of the Climate Vulnerable Forum who fought to change the threshold from 2 degrees to 1.5.”

I remember them chanting “1.5 to stay alive”, because two degrees was a death sentence for too many places and people. The officially powerless swayed the officially powerful, and 1.5 degrees was written into the treaty and has became a familiar number in climate conversations ever since. Even though we’ve crashed into that 1.5 threshold, far better that it be set there than at 2 degrees, in which case we might well be complacent in the face of even more destructive temperature rise.

It takes far more than storytelling to get where we need to go, but how we tell the stories is crucial. I asked the climate policy expert Leah Stokes of UC Santa Barbara about the impact of Paris and she told me: “When small island nations pushed for 1.5 degrees as the target, they also requested the IPCC [intergovernmental panel on climate change] write a special report on what policy would be required to get there. That report came out in October 2018, and rocked around the world with headlines like ‘we have 12 years’. It changed the entire policy conversation to be focused on cutting pollution in half by 2030. Then, when it came time to design a climate package, Biden made it clear that his plan was to try to meet that target. You can draw a line between small islands’ fierce advocacy through to the passage of the largest climate law in American history.”

That’s how change often works, how an achievement ripples outward, how the indirect consequences matter as well as the direct ones. The Biden administration tried to meet the 1.5 degree target with the most ambitious US climate legislation ever, the Build Back Better Act that passed Congress after much pressure and conflict as the Inflation Reduction Act. Rumors of the Inflation Reduction Act’s death are exaggerated; some pieces of its funding and implementation are still in effect, and it prompted other nations to pursue more ambitious legislation. In the US, state and local climate efforts, have not been stopped by the Trump administration. Globally not nearly enough has been done to stop deforestation, slash fossil-fuel subsidies, and redesign how we live, move, and consume.

All this made me go back to my basic principles. I started a new thread on all this, quoting from my book Hope in the Dark: "The analogy that has helped me most is this: in Hurricane Katrina, hundreds of boat-owners rescued people—single moms, toddlers, grand- fathers—stranded in attics, on roofs, in flooded housing projects, hospitals, and school buildings. None of them said, I can’t rescue everyone, therefore it’s futile; therefore my efforts are flawed and worthless, though that’s often what people say about more abstract issues in which, nev- ertheless, lives, places, cultures, species, rights are at stake. They went out there in fishing boats and rowboats and pirogues and all kinds of small craft, some driving from as far as Texas and eluding the authorities to get in, others refugees themselves working within the city. There was bumper-to-bumper boat-trailer traffic—the celebrated Cajun Navy—going toward the city the day after the levees broke. None of those people said, I can’t rescue them all. All of them said, I can rescue someone, and that’s work so meaning ful and important I will risk my life and defy the authorities to do it. And they did."

It's an example that illustrates one point: that what we do is worth doing even if we can't do everything and save everyone. It's a real story about how hundreds to thousands of volunteers showed up and saved thousands to tens of thousands of stranded souls. It's not necessarily a perfect example of how change works at its best. For example, an individual might help one enslaved person to freedom, and even helping that one person might mean being part of the Underground Railroad, part of a collective effort, but a person who joined the abolitionist movement would ultimately help end the very institution of slavery in the United States.

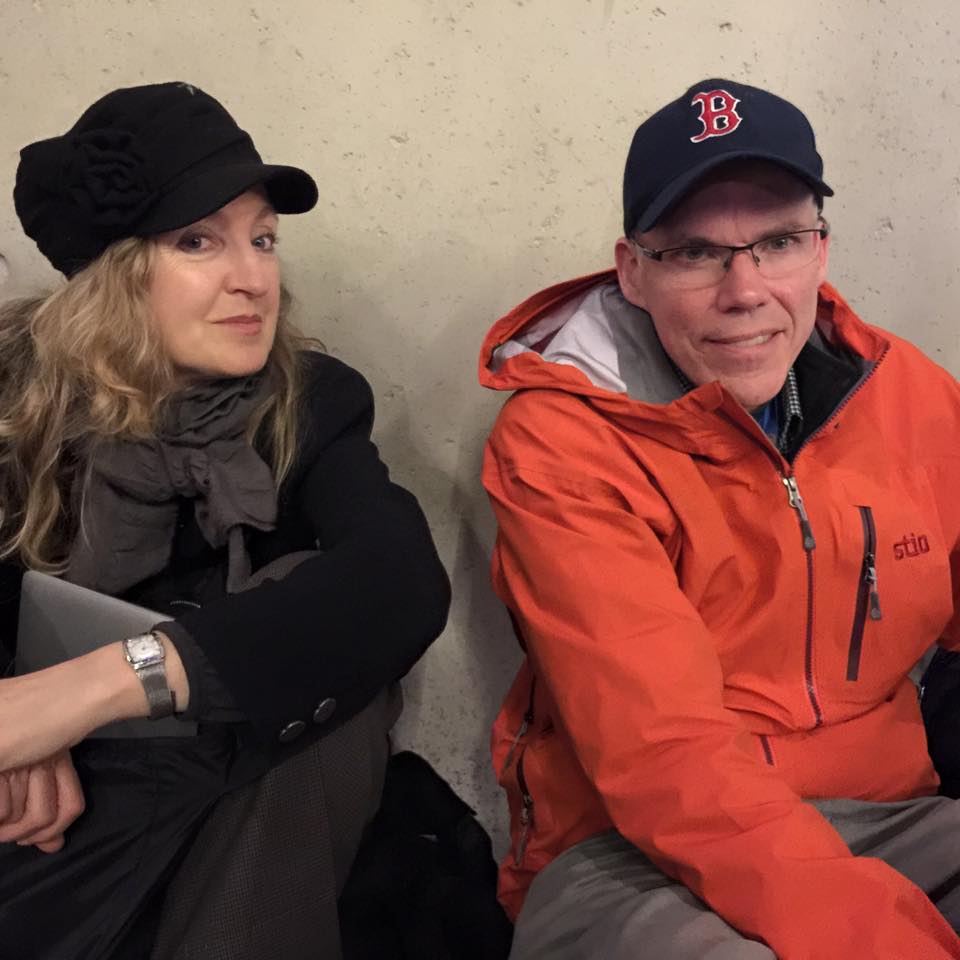

It was while I was at the Paris Climate Treaty, while I was sitting on a concrete floor with Bill McKibben, who's done more for the climate than almost anyone else on earth, and longer too, that I first heard him say something he's said many times since. (I think this picture of us is at the time he actually said it, and yes, that's a Boston Red Sox cap he's wearing.) Someone walked over, peered down at us on the floor, and said, "what's the best thing I can do for the climate as an individual?" Without missing a beat, Bill replied, "Stop being an individual," by which he meant join something. For most of us, our power to change the world comes as collective power, when we're members of movements, organizations, uprisings.

I realized at the National AIDS Memorial benefit I wrote about in my last epistle here, while looking at the AIDS quilt pieces, that while my friend Cleve Jones (whose inspiringly fiery talk was a Meditations-in-an-Emergency essay here ) has often spoken to me with what sounded like despair that he has never actually given up and he hasn't now. He's not just not given up; he's catalyzed resistance for decades. Jarvis, my friend who's been in the California prison system since he was 19 (he's 63), hasn't given up either. The climate activists in the South Pacific who have often been told to give up because sea level rise will swallow their nations declare, "We’re not drowning. We’re fighting."

Those who have not given up are an inspiration to the rest of us. Those who have surrendered in advance are a danger, because both hope and despair, solidarity and surrender are contagious. Which does not mean recommending foolish optimism; it means advocating for stubborn resistance, and recognizing that often that defeatism presumes it knows what can happen, that history is linear, that the future will be some expansion or contraction of something clearly present now. In fact, history zig-zags, leaps, ducks, and has offered extraordinary surprises that we normalize in retrospect. And what turns out to matter has often been invisible or regarded as insignificant in the present.

Right now the equivalent of the Cajun Navy is all the people stepping up in solidarity with those under attack by ICE. I remain profoundly moved and even awed by the strength of that solidarity from Minneapolis to New Orleans, Los Angeles to New York, Chicago to Charlotte. But the climate movement has not stopped doing its good work either.

My friend Saket Soni, who founded Resilience Force, a remarkable organization that is at once a labor-rights organization, an immigrant-rights organization, and a post-climate-disaster rebuilding organization that brings immigrant communities to impacted places, has started his own newsletter, which I recommend:

and throughout the last six months, I've read stories of heroic solidarity with immigrants, refugees, and the Brown and Black people ICE treats as such, even when they're citizens, even when they're Native Americans.

This resistance is a gift to all of us and a reminder. This is who we can be. This is who we have been. This is who we must be in the face of the forces of destruction. That means the attack on the most vulnerable. And the attack on the earth itself.

p.s. I recommend this guy, who's on Facebook and BlueSky. Climate action proceeds in a thousand different ways, and places, and no overview article can sum it all up. But someone like Assaad Razzouk can track a lot of the highlights and does beautifully.